The Joy of Pattern Matching

Pattern Matching is a beautiful way to specify the different behaviours a function has depending on its arguments.

By other words, Pattern Matching is the dispatch mechanism of deciding the correct definition of a function to be applied based on the presence of the parts of a defined pattern.

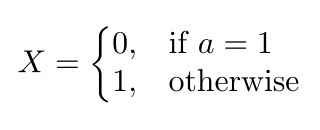

This might sound a bit too high level, or confusing, but it’s pretty straightforward and since it has roots in mathematical notations, you might have seen it before:

The definition of this function is very obvious. The key point here is to understand that although we have “if’s” in there, this is not the same as an if-else. X(1) is defined to return 0, and X for any other argument is defined to return 1.

In Haskell, this very same function is defined as:

f 1 = 0

f _ = 1The _ is called wildcard. It is used when the argument is irrelevant for the function behaviour and return value.

In Java, we would do:

int f(int x) {

return x == 1 ? 0 : 1;

}Although the Haskell equivalent is arguably more elegant and readable, this one in Java looks alright. But note that if the function happens to have to deal with more cases, the Java solution has to change to either if-else or switch-cases, which will become ugly.

It is NOT a switch-case

Pattern matching is not really the same as a switch-case. They are fundamentally different.

A switch-case reads as “given x, case it matches this value, perform this computation” while that pattern matching reads as “the function f, given an argument that matches this pattern, returns the following”.

On Lists

The previous example is a classic pattern matching on primitive types. But there is much more.

Imagine that having a list of numbers, we want to divide every two elements, in sequence. If the second element of the pair is 0, the first should be divided by 7. If there is one left alone, it is divided by 3.

So we have to think about:

- the empty list case

- the case of having a list with a single element

- the case where the second element is 0

- the default case

everyTwo [] = []

everyTwo [x] = [x/3]

everyTwo (x:0:xs) = everyTwo (x:7:xs)

everyTwo (x:y:xs) = x/y : everyTwo xsIsn’t this neat?

On Custom Types

This means the ability to pattern match a custom type by checking its fields/parts.

For example, being Singer a type that has a name, the function singVerse will be different if the person singing is Michael Jackson or 50 Cent, otherwise, it will solely be the literal verse:

data Singer = Singer {name :: String} deriving Show

singVerse :: Singer -> String -> String

singVerse (Singer "Michael Jackson") verse = verse ++ " hihi!"

singVerse (Singer "50 Cent") verse = verse ++ " yeahh"

singVerse _ verse = verseHaskell programmer: yeah, this can be simplified by omitting the verse and making the general case returning the id function. For the purpose of the example, clarity is more important.

In Java, this would look like this:

class Singer {

private final String name;

public Singer(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public String singVerse(String verse) {

if (name.equals("Michael Jackson")) {

return verse + " hihi!";

}

else if (name.equals("50 Cent")) {

return verse + " yeahh";

}

return verse;

}

}Note: this serves for the example. In the context of a real project, you should consider the strategy pattern here.

By looking at both solutions, do you see how different they are and how pretty and more maintainable the first is?

On Polymorphism

The next step is pattern matching in order to achieve polymorphism.

Consider different shapes and how you calculate their area.

data Shape = Rectangle Double Double | Square Double | Circle Double

area :: Shape -> Double

area (Rectangle width height) = width * height

area (Square sideLength) = sideLength^2

area (Circle r) = pi * r^2It’s very clear and straightforward.

I would translate this to Java by having an interface Shape containing double area();``` and Rectangle, Square and Circle as implementations.

However, I do prefer the way it can be done in Haskell. In five lines we have all of this logic defined in a clean and clear way.

On Filtering

Pattern matching can also be used as a filter.

Imagine we have a list of Shapes and we want to get only the Circles ones:

onlyCircles :: [Shapes] -> [Circles]

onlyCircles shapes = [Circle r | Circle r <- shapes]On Binding

In Haskell, you can also apply pattern matching when binding values to a synonym.

Let’s imagine the where you want to check if the first and last element of a given list are the same:

firstEqualsLast :: Eq a => [a] -> Bool

firstEqualsLast [] = False

firstEqualsLast xs = f == l

where (f, l) = (head &&& last) xsNote that (head &&& last) xs return a tuple, which is matched by (f,l).

Conclusion

Pattern matching really is a joyful feature. It doesn’t fit every problem but it is no doubt a neat and joyful way of writing beautiful, declarative and readable code.